I just finished Skyping with my son and daughter-in-law in The Netherlands. It is always a joy to speak with them, and after each time I do I miss them more. They both are teaching—he music in an international school, and she English in a public school. While my son is happy with (if exhausted by) his work, my daughter-in-law is having her doubts. It seems educationally Holland is caught up in the same testing fervor we are in the U.S. Her middle-school-aged students’ performance is judged entirely on a series of national standardized tests. And those tests, consisting of listening to and watching videos and then answering multiple-choice questions, are designed with similar “tricks” so characteristic of the old SAT. (Tricks that necessitated test prep not so much on subject matter but on how to game the exam.) For each English question on the test there is always an official “right” answer, but there is often also a possible plausible alternative. “A” may be “correct,” but “B” or “C” might also make sense.

I just finished Skyping with my son and daughter-in-law in The Netherlands. It is always a joy to speak with them, and after each time I do I miss them more. They both are teaching—he music in an international school, and she English in a public school. While my son is happy with (if exhausted by) his work, my daughter-in-law is having her doubts. It seems educationally Holland is caught up in the same testing fervor we are in the U.S. Her middle-school-aged students’ performance is judged entirely on a series of national standardized tests. And those tests, consisting of listening to and watching videos and then answering multiple-choice questions, are designed with similar “tricks” so characteristic of the old SAT. (Tricks that necessitated test prep not so much on subject matter but on how to game the exam.) For each English question on the test there is always an official “right” answer, but there is often also a possible plausible alternative. “A” may be “correct,” but “B” or “C” might also make sense.

My daughter-in-law gave an example: the class was shown a clip from a documentary of a solider struggling to fit a chimpanzee into a spacesuit before it is sent into space. The scene was disturbing—the chimp is shown screaming and trying to escape. The soldier seems at a loss as to what to do, and speculates that perhaps the chimp is upset because not only was it taken from its family, but now it was taken out of the facility in which it had been living. After seeing it, the students were asked what was the net takeaway. The supposed right answer is that the soldier doesn’t know what to do. But one of the other choices is that the chimpanzee is homesick. Any child who chose that answer was marked wrong. So the stronger emotional aspect of the video—the animal’s distress—the one that surely had most impact on anyone watching, was discounted.

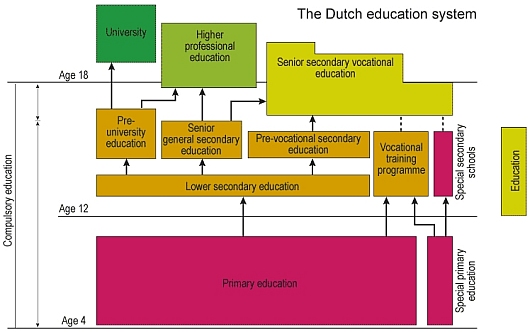

What is especially upsetting to my daughter-in–law is that so much depends on these tests. (Testing is also used in a more basic way in Holland to track students into different levels of education.) Even though she knows some of her students are more proficient in English than their test scores would indicate, she can not pass them if they fail. And if they fail, they must repeat the entire year. And if they fail again, they must leave the school. English is one of three essential subjects in the Dutch schools (the others are Dutch and math). It is understandable that, in today’s global economy, it is important for the kids to know English. But so much time is spent on the tests, and (as here) on test prep, that there is not enough time left over for conversation or reading more interesting materials. No time to make learning English less of an anxiety-ridden chore.

At least in the U.S. there has been some movement away from the mania to quantify achievement through testing and the use of exams to judge teachers’ performance. One hopes it is not too late to repair what they have wrought: the diminishment of education and the stigmatization and demoralization of teachers. It is as if the people who devised the test-based curriculums had never been inside a classroom, never had a good teacher, or have no understanding of the way children actually learn. Or, perhaps, more cynically, as we know some of them send their sons and daughters to private schools that do not emphasize standardized tests, they feel this approach is good enough for everyone else’s kids.

Even if increased testing started as a well-intentioned effort to raise standards, to insure that all children were taught the basics, it has devolved into a joyless, dehumanizing, second-class system. Cold comfort that it exists in other countries as well.